Almost immediately upon his arrival in New York City, however, Illich quite literally took a radical turn. Instead of settling in Princeton, 50 miles to the south in central New Jersey, he took the 'A' train to northern Manhattan. And there, for the next 5 years, he would serve as a parish priest, paying most of his attention to the neighborhood's burgeoning population of Puerto Ricans. And it was this ministry, writes Christopher Shannon in a 2004 essay, "The Death and Rebirth of Ivan Illich," appearing in a Web publication called Books & Culture, "that provided the intellectual foundation for all his subsequent writings."

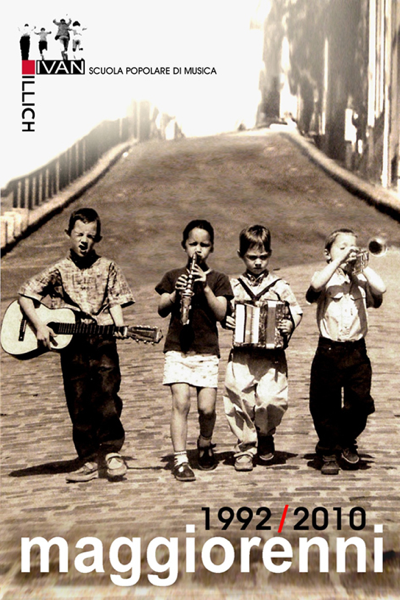

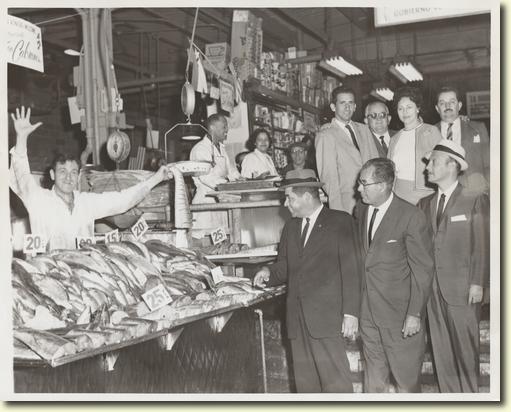

While visiting family friends in New York, he would later tell interviewers, Illich had heard from an African-American maid about mounting tension between the city's blacks and the many newly-arrived Puerto Ricans. Curious, Illich visited a then-thriving Puerto Rican street market in East Harlem and very quickly, these Caribbean immigrants struck him as more fascinating than medieval alchemists. The market was La Marqueta, originally a gathering of Italian-owned pushcarts that eventually consisted of nearly 500 vendors crammed into five buildings situated beneath the elevated railroad tracks running up Park Ave. between East 111th and 116th streets.

[Photos, from top): Bettman/Corbis (1968); http://www.literanista.net; NY State Archives]

Puerto Ricans had moved to the city in large numbers during WW2, many of them to work in jobs previously held by men and women fighting overseas. After the war, many of these new workers stayed on, but in New York City, they didn't fit the typical immigrant mold, as would soon be portrayed so memorably in the Broadway musical West Side Story. From the song "America":

Boys: I think I go back to San Juan

Girls: I know a boat you can get on

Boys: Everyone there will give big cheer

Girls: Everyone there will have moved here

Because New York was only a few hours' flight from the Caribbean, Puerto Ricans didn't necessarily consider the mainland their permanent home, as had most of their European predecessors, whose journey involved many days on a ship. What's more, their ways of living were new to New York. In, Puerto Rico, daily life was spent mainly outside, in a sunny clime and mostly around, not within, small, relatively flimsy homes. (Why build permanently in the face of frequent hurricanes?) But now, their eating, socializing, and playing games, and their children playing so openly out in front of apartment buildings was not always appreciated by their New York neighbors.

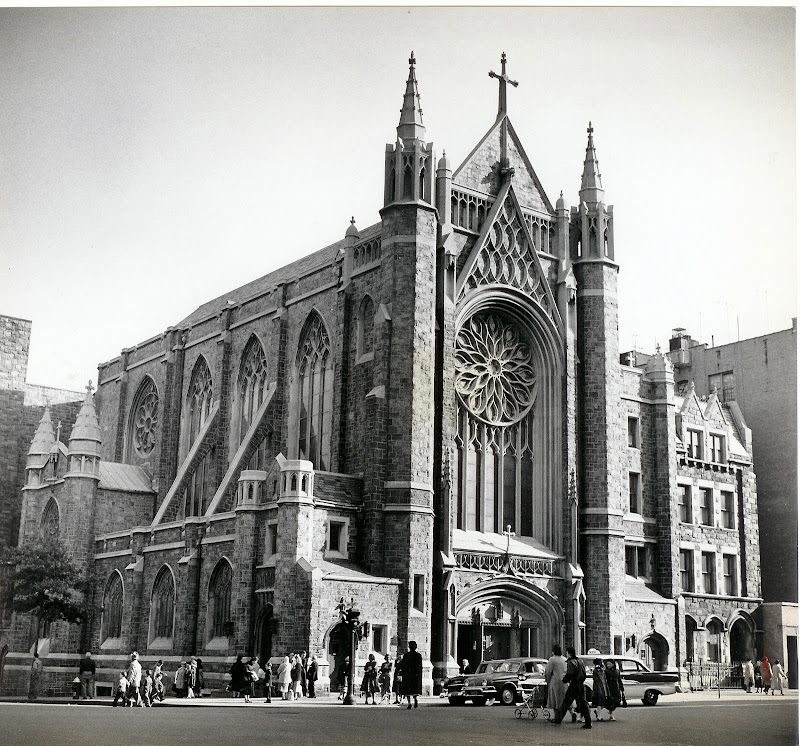

Using his connections with the New York diocese under Cardinal Spellman, Illich managed to get himself posted to a church where he might serve these newcomers as well as learn more about their culture. He was named an assistant priest at Incarnation Parish, located on St. Nicholas Ave. at 175th St., practically in the shadow of the George Washington Bridge. Here is the church as seen in 1957:

Incarnation had long served a flock of fairly conservative Irish. Washington Heights, as the neighborhood was called, also had become home to a fair number of Germans, many of them Jews who'd fled to America before the world war. (Among them, as we recall, was the family of Henry Kissinger.) Eventually, Illich's mother would move to this neighborhood, too, and spend her last years there. (Interestingly, in light of Illich's enduring interest in the Middle Ages, The Cloisters, a marvelous museum devoted to that era, is in this neighborhood, a few blocks to the north of the bridge on a cliff overlooking the Hudson River.) Like many NYC neighborhoods, Washington Heights saw many of its residents eventually leave, but they took with them many memories, as seen here. (The neighborhood is largely Latino, now, but last we visited, a few Irish bars were still operating and in the park that surrounds The Cloisters, German was still to be heard occasionally.)

Illich's time at Incarnation is recounted with much color by Francine du Plessix Gray in her 1970 book, Divine Disobedience. She recalls how the pastor of Incarnation, a Monsignor Casey, thinking that the name Ivan sounded "Communist," insisted that his new curate call himself John Illich.

John Illich's energy and devotion at Incarnation became legendary, Gray reports. One of his colleagues there told her that "living in the same parish with John Illich was 'like riding a Piper cub with an atom bomb under the seat.' Illich climbed stairs three at a time and never walked through the rectory, but swept through it like a tornado. He rose earlier, questioned more, worked harder for the Puerto Ricans than any man in the diocese. ... The Puerto Ricans idolized him ... he was Mr. Puerto Rico, their Babe Ruth."

In 2003, we came across a memoir of growing up Catholic in Washington Heights in the 1950s, by a Richard O'Prey. (This memoir no longer exists as we found it, but it has been archived in the Wayback Machine, an archive of old websites. Mr. O'Prey also seems to have published it in book form.) He recalled Illich as an erudite priest - though it appears he may have misremembered Illich's story about fleeing pursuers of some sort; if Illich was forced to escape anyone, it was likely the Nazis:

Father Ivan Illich, a fugitive from the Iron Curtain, was the final

member of the staff at Incarnation. Father Illich spoke heavily accented

English, but he was reputed to be an intellectual. In later years, he

would prove that assertion by writing several books on education and

Church reform. In the early 1950s he contented himself in saying Mass

with a piety and deliberation that went far beyond his peers. No one

could accuse him of garbling his Latin or hurrying the rubrics of the

Mass. His account of eluding border guards and escaping the Iron

Curtain, was fascinating. It also humanized the conflict that we heard

about in Europe. For his bravery and audacity, he won our respect and

admiration.

Here is what appears to be the New York Times' first mention of Illich, in March, 1953:

Serving society couples, we imagine, was only a sideline. Illich's main accomplishments were in and on behalf of the Puerto Rican community, which still, if unknowingly, celebrates his remarkable efforts almost 60 years later. Illich was instrumental in bringing that struggling community into the fold of the wealthy, Irish-dominated New York diocese. Caribbean and Latin American Catholics celebrated their religion quite differently from Europeans, singing different songs, interpreting the images and lives of certain saints quite differently, and even understanding the hours of the day in a different way. (Illich understood that it was too much to expect islanders to arrive for Mass "on time" with the same precision that most New Yorkers took for granted.) Unlike many of his fellow churchmen, Illich actually bothered to learn the Spanish language - very well and incredibly quickly, Gray reports. The diocese sent him to a Berlitz course downtown, but Illich breezed through those lessons and found the best language training to be simply mixing with his parishioners out in the streets. (It helped, we imagine, that he already knew Italian.) Equally important, he made a point of getting to know the culture of Puerto Rico, from his parishioners and by spending summer vacations on the island, owning a shack there and traveling its rural byways on horseback and by foot.

It was during one of these visits that he learned of a man who would be tremendously influential. This was sociologist Joseph P. Fitzpatrick, S.J., whom we've written about here recently. As Mr. Shannon tells it in his "Death and Rebirth" article, which reviews a collection of essays published in 2002, The Challenges of Ivan Illich, Fitzpatrick helped greatly to further Illich's education. With a degree from Harvard, Shannon writes,

Fitzpatrick was among the first generation of Catholic priests who saw immersion in secular learning as essential to the task of making the Church relevant to the modern world. [...] Though educated to the highest European standards in history and philosophy, Illich actually knew little of modern social theory; Fitzgerald modestly takes credit for introducing Illich to the works of Durkheim, Weber, and the other great writers of modern sociology. [...] On one of his visits [to P.R.], Illich learned of Fitzgerald as the only other New York-based clergyman to go to Puerto Rico to study the cultural background of the immigrants. Back in New York, Illich and Fitzgerald struck up a friendship and began to collaborate on a variety of innovative pastoral projects.

Shannon sees the Illich-Fitzpatrick partnership working in ways that differed significantly from other Church-led social-reform efforts of the time:

Against the assimilationist ethos of the early civil rights movement and anticipating the Second Vatican Council's endorsement of "inculturation," Illich argued that the Church could best serve the newly arrived Puerto Ricans by helping them to sustain their traditional liturgical and devotional practices in their new environment. Unlike the progressive, "social justice" Catholicism of the late 1960s, Illich saw culture, rather than economic inequality, as the starting point in the pastoral care of the poor. [In Challenges, Illich collaborator Lee] Hoinacki notes Illich's academic training in the history of liturgy, and argues that Illich "understood … that the most ominous expression of secularization in the West was … the decline of liturgy, the routinization and emptying out of religious ritual in the churches." The liturgical lens through which Illich read modernity may account for the difficulty so many secular intellectuals have had in understanding, much less accepting, his social critique.

[...]

At the heart of Illich's pastoral vision lay the conviction that ministering to the poor requires not so much service as presence. Illich sought not to help the poor, but to be poor. Being poor meant many things, from the biblical ideal of the poor in spirit to a more anthropologically informed notion of cultural poverty, or the abdication of one's cultural assumptions in order to immerse oneself in the life of the poor. Fitzgerald and Illich sought to embody this ministry of presence in their first collaborative outreach project, El Cuartito de Maria, or The Little House of Mary. Illich arranged for Incarnation to rent an apartment in one of the tenements heavily populated with Puerto Rican (potential) parishioners. Women from the parish volunteered to watch and play with children so that mothers could work or run errands, but the purpose of the project was neighborly rather than vocational. Illich insisted that establishing personal relationships with the immigrants was a more important ministry than any program of material or spiritual uplift.

"By the standards of 1950s social work," Shannon explains, "El Cuartito de Maria did not do much to improve the lives of the poor, but then that was never Illich's intention. Much to the confusion of his church colleagues, and later his secular interlocutors, Illich rejected not only the idea of improvement, but the very language of doing and making, both of which he saw undermining authentic human relationships in the modern world."

From what we've read, especially in The Rivers North of the Future, where Illich elaborates on the parable of the Good Samaritan, this observation rings quite true. Authenticity in relationships - true friendship, as he might have put it - is precisely what Illich idealized in opposition to the "liberal fantasy" of treating and understanding people as mere instances of a class that experts view as needy of professional therapies and services. The idea of Illich rejecting "the very language of doing and making" is not one we've heard before, but it does seem to resonate with Illich's idea of foregoing power in favor of informed, contemplative, fully aware impotence.

We recently came across Fitzpatrick's side of the story, as related in his own book The stranger is our own: reflections on the journey of Puerto Rican migrants. A good chunk of this book is available via Google Books, and on page 16, we read of the two men's first encounter:

In the spring of 1953, I was sitting in my office in Keating Hall when Father William Lynch, S.J., then editor of Thought, the Fordham University Quarterly, came into my office. He said: "There is a young priest in my office and he would like to meet you. His name is John Illich." ... And so I met the man who was to have a profound influence on me and on the Church during my generation. I walked into Father Lynch's office and I was immediately struck by the appearance of the man: tall, exuding energy and tension, and intense in conversation. "I followed you all over Puerto Rico," he said, "and I read the report you left with Bishop Davis. You are the one person I wanted to meet when I came back." [...] He then described for me his whirlwind month in Puerto Rico. It was far different from mine during which I was accompanied from door-to-door of prominent people, introductions arranged ahead of time. Illich walked over miles of rural roads, took to horseback, visited towns in remote mountains and crowded urban barrios. In his conversation with me, he began to comment on the customs and culture of the people. For a person who was neither an anthropologist nor sociologist, his perception of the culture and lifestyle of the Puerto Ricans was remarkable. I said to myself, "This is a man I want to keep in touch with." We talked for almost two hours, during which I learned many things I had not known about aspects of Puerto Rican life. After he left, Father Lynch asked me, "What is your impression?" I don't know what it was that prompted me to say it; I know nothing at the moment of Illich's background. I replied, "Bill, he reminds me of some of my brilliant Jewish intellectual friends. I wonder if there is something Jewish about him!" Years later, I was to meet his mother and learn that she came from Sephardic Jewish ancestry. She had become a Catholic to marry Illich's father and she remained a devout Catholic until her death.

Fitzpatrick also recalls the creation of what he calls El Cuartito de la Santisima Virgen, or "The Little Room of the Most Holy Virgin": Illich "encouraged a group of the young women to fix up the apartment with pictures and items reminiscent of Puerto Rico, and just be there to allow the children and mothers to come by, to mind the children when mothers went shopping; in brief, to create a familiar, neighborhood place where the people could gather with no formality, but which was carefully organized by the young women. ... It was a remarkable example of receiving the Puerto Ricans as our own, in a situation where they were very much at home among their own. After Illich left Incarnation parish and went to Puerto Rica (November 1956), the interest faded and eventually El Cuartito disappeared."

Fitzpatrick recalls working with Illich on a "slide show" to help migrant workers in New Jersey "in their social and religious life. Illich conceived of an arrangement of slides depicting experiences of the farm workers, and a cassette which would provide an explanation for the workers of the experiences depicted in the slides. We worked very hard on this. I wrote the text for the cassette. ... At the last moment, it never came off. ... It was a brilliant Illich idea which, for some reason, was aborted." (We imagine that Fitzpatrick probably meant simply a tape recorder, not a cassette, for the latter had yet to be invented.)

Illich's real triumph regarding the city's Puerto Ricans - and the New York diocese itself - was the San Juan Fiesta. As Fitzpatrick describes it, this was a celebration in honor of the patron saint of Puerto Rico. It had begun in 1953 and continued for two years in St. Patrick's Cathedral, down on Fifth Ave. "Illich said this was ridiculous and that a fiesta like this should be held outside with processions and civic celebrations." And so, in 1956, the event was moved to the Fordham campus, up in The Bronx, complete with a large procession and Mass celebrated by Cardinal Spellman - a key backer of Illich then and when he had moved on to Mexico - and even a sermon given by Spellman in Spanish. Thanks partly to Illich's touring Puerto Rican neighborhoods with a sound truck, some 30,000 people showed up for this event - a good ten times more than had been predicted by one church official.

This event made Illich nothing less than a hero within the diocese, for he had managed to bring off a rapprochement between the Puerto Rican flock and the Irish-led diocese in way that surprised both sides. In fact, this yearly event continued to be held year after year, every June 24, more or less, and it continues today, more or less. It's now known as the Puerto Rican Day Parade and it's held in June on Fifth Ave. by Central Park.

Illich's triumph led to his being named as vice-rector of the Catholic University of Puerto Rico. And his taking that post, Fitzpatrick recalls, seemed to be appropriate, given South America's increasing importance to the U.S. and the Church and the potential for Puerto Rico to serve as a bridge between the two continents. Here is how the New York Times covered the news:

As anyone who has read much about Illich knows, his time in Puerto Rico was fertile yet stormy. Spellman visited the island and thanks to Illich, was received with thousands cheering his motorcade's entry into San Juan. It was in Puerto Rico, too, that Illich and Fitzpatrick co-wrote (with a William Ferree) a book called Spiritual care of Puerto Rican Migrants, which is available for viewing on Google Books (Google sells this book in electronic form, too, for $10.) It also was in P.R. that Illich had his first close look at - and serious doubts about - compulsory schooling, a line of thinking that eventually led to Deschooling Society. (Someone named Anandita Bajpai did their master's thesis in 2008, at the University of Vienna, about The Catholic Church as an Education Provider in Puerto Rico 1948-1960; it's available online in PDF format. The thesis advisor: Prof. Dr. Martina Kaller-Dietrich, the author, in 2008, of a biography of Illich.)

And it was in Puerto Rico, too, that Illich ran afoul of Church authorities when he publicly argued against their plans to start a political party opposed to birth control. Illich believed the Church had no business getting involved in politics, especially at a time when there was so much controversy over a Catholic (John F. Kennedy) running for president of the U.S. The resulting controversy led Illich to leave not only his university post but the island of Puerto Rico itself. Working with Fitzpatrick, he selected Cuernavaca, Mexico, as home for the Center for InterCultural Documentation, or CIDOC, which would remain there until its voluntary closing in 1976.

Interestingly, while Incarnation's own website cites the church's role in the history of Puerto Ricans in New York, it makes no mention at all of either John or Ivan Illich.